NAM: Looking at Horror

by Disphotic

This is the first of several extracts from the introductory essay to my latest project, Vietnam Deprimed. It explores the notion of horror, its representation in visual culture and media, and how weapons are frequently foregrounded while images of the destruction they cause to the human body are hidden in various ways.

On encountering a sight like a vicious wound or mutilated corpse most people feel horror, a mixture of disgust and fear. Horror is a variable quantity, and what triggers this response is contingent on the make-up of the individual viewing it, their background history; their psychological state at the moment of encounter and myriad other factors. A doctor used to treating trauma wounds may be less appalled than someone who has never seen a gunshot wound. For some people this experience can trigger other emotional responses, perhaps embarrassment at viewing the suffering of another, or, inversely, a feeling of voyeurism at witnessing something that it is taboo to observe.

Horror is ‘always subject to historical change’ [Taylor p.2]. Only a few centuries ago, scenes of horror were more common in European societies than they are now and therefore more normal. Healthcare was less effective and disease rife, death a distinct possibility at many stages of life. Wars were fairly regular events, mutilation and violent death were so common as to be parts of the judicial process, and such punishments were often carried out as public spectacles for all to witness.

The last two centuries however have seen advances in healthcare which have radically reduced mortality and changes in justice that have led to ‘the disappearance of the tortured, dismembered, amputated body … exposed alive or dead to public view’ at least in most of the developed world [Foucault, p.8]. At the same time, much of the developed world has experienced a relatively long period of uninterrupted peace. Apart from random accidents and freak violent acts, sights of horror have disappeared from our lives.

Execution of Charles I

The disappearance of these sights from view, combined with the simultaneous rise of mass media and global communication means that, for most people, our encounters with horrors like conflict will be predominantly through images. Sontag argues that, as a result, ‘the understanding of war among people who have not experienced [it] is now chiefly a product of the impact of these images’ [Sontag, p.19].

This is significant in many respects, not least the fact that our encounters with scenes of horror now pass through numerous layers of filtering,: from what the journalist in the field chooses to photograph or film, to what military or government handlers may allow to be filed, or to what an editor chooses to run. Equally, such dependence on images is problematic because however accurately they may depict a terrible scene, photographs are only ‘at most a trace and not the thing itself’ [Taylor, p.5].

Photographs can still generate a sense of horror, but they do so in a different way to encountering such sights in real life. Most obviously with a still photograph we are able to sit and study scenes that may have only been viewed for a fraction of a second by the photographer. This can variously heighten or undermine their shock value, depending on the image in question. Photographs also problematically exacerbate the voyeuristic tendency intrinsic in a witnessing horror because they ask ‘viewers to stare at the scenes with impunity’ [Taylor, p.14].

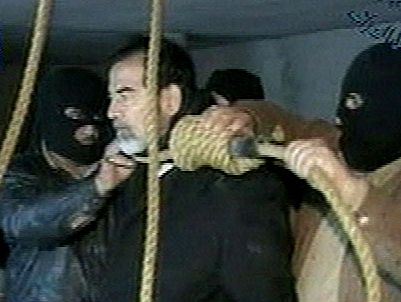

Execution of Saddam Hussein

Despite these flaws in the representational ability of photography to show terrible things, it is important that we use it to do so, and that we look at the images that result. The alternative of simply not knowing about horrific events, particularly a man made phenomenon like war – a phenomenon in which we are often to some extent complicit – is far more troubling. As Sontag writes ‘…war tears, rends. War rips open, eviscerates. War scorches. War dismembers. War ruins.’ [Sontag, p.4]

Not to know this, or only to know it in the abstract sense of knowing something one has been told but never seen (even in a photograph), is courting disaster. John Taylor aptly sums up the problem: ‘…the use of horror is a measure of civility. The absence of horror in the representation of real events indicates not propriety so much as a potentially dangerous poverty of knowledge’. [Taylor, p.11]

———-

Short bibliography:

John Taylor, Body horror

Susan Sontag, On the Suffering of Others

Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish