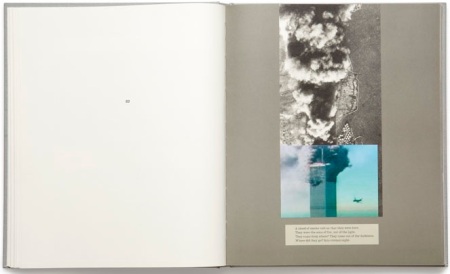

This is the second of several extracts from the introductory essay to my latest project, Vietnam Deprimed. It explores the notion of horror, its representation in visual culture and media, and how weapons are frequently foregrounded while images of the destruction they cause to the human body are hidden in various ways.

Vietnam was notable because of the way the media were able to bring the brutality of the war onto the front page, and into people’s homes. It was the first television war, and it was also the first largely uncensored (or to be more accurate ineffectively censored) war. There have been innumerable changes in the way the media function since 1975, but there are three changes that have emerged as a direct result of the Vietnam War and which have detrimentally affected the way the media represent horror.

First, far greater restrictions are now placed on journalists covering wars. The war in Vietnam was lost by the media, or at least that was the story the US military consoled itself with, and correspondents congratulated themselves with. True or not, the belief in this has subsequently led the armed forces to impose greater restrictions on correspondents. During the Falklands War of 1982, for example, the Ministry of Defence only allowed a limited number of correspondents to join the naval task force, dressed them in military garb and attached them to specific units. The media simply had to accept these conditions because the military ‘and only it controlled access to the warzone’. [Knightley, p.478]

Since the Falklands War this technique, known as ‘embedding’, has become standard practice because it enables the military to keep track of what journalists are able to see and report, and places them in such close proximity to soldiers that a degree of bonding is inevitable. The result is that the stories journalists are able to report, and the photographs that they are able to take can be directed by military priorities, and the negative elements of war, particularly death and injury, are more easily filtered by ‘censorship at source’. [Knightley, p.479]

A B-52 ‘Stratofortress’ strategic bomber dropping bombs on North Vietnam

The second development that has compromised the media’s ability to depict war’s horrors is the increasing use of remote and long range methods of killing. Again, Vietnam was the genesis of a practice which continues to the modern day. The ground war in Vietnam was violent, visually spectacular and, as it turned out, unwinnable. Towards the end of the war the US military turned instead to carpet bombing North Vietnam. Not only did this result in fewer American casualties, it was also impossible for journalists to report the effects, even when US bombers started illegally bombing neighboring Laos and Cambodia.

This approach has continued. A present day example is the Unmanned Aerial Vehicle or ‘Drone’ attacks carried out in remote areas of Afghanistan and, again illegally, Pakistan. ‘Drone’ aircraft are remotely piloted by operators hundreds or thousands of miles away, and their attacks take place without warning and in areas journalists have difficulty reaching. For the military this is the best of both worlds, with no danger of dead American pilots, and little likelihood of journalists bringing back inconvenient photographs of any bystanders killed in attacks. For Taylor this is part of a process of ‘derealisation’, where war is depicted as being ‘acted out by machines rather than on the bodies of people’ [Taylor, p.158]

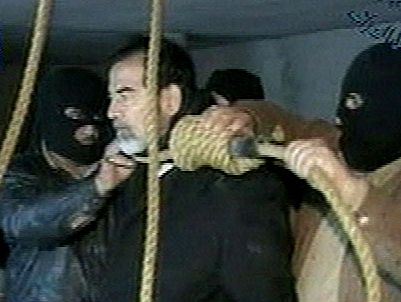

The third important development to emerge since Vietnam is the increasing tendency of the press to self-censor. This can be understood partly as a backlash against the graphic coverage of the Vietnam War. Media self-censorship is related to a wide range of issues, commonly banded together under the term ‘propriety’. Press propriety is often construed as a moral matter, but as Taylor states, ‘the press is not dedicated to forcing its audience to view horrific imagery and has no use for it in a regular moral or improving agenda of its own’[Taylor, p.3], rather propriety is a matter of pragmatism or good business.

An MQ-1 Predator drone firing a missile

The most obvious respect in which this is true is that self-censorship is often necessary in order to facilitate present or future co-operation with outside organisations. For example, advertisers are unlikely to want their advertisements for, say, skincare products opposite an image of someone immolated by napalm. Embedding is also a good example of this pragmatism, as a photographer may resist publishing controversial imagery of a war if it may damage their relations with the military and make future collaboration difficult. Don McCullin was repeatedly denied access to cover the Falkland’s War, almost certainly because ‘his type of war photography threatened the image of war that the military wanted to convey’. [Knightley, p.479]

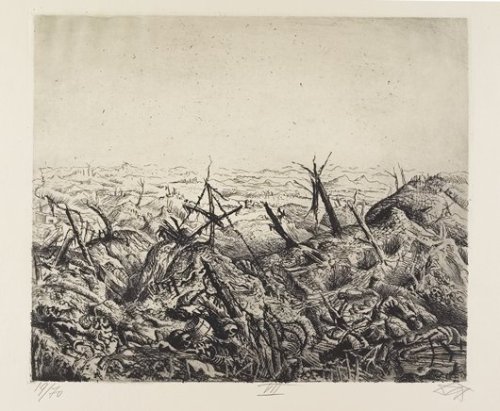

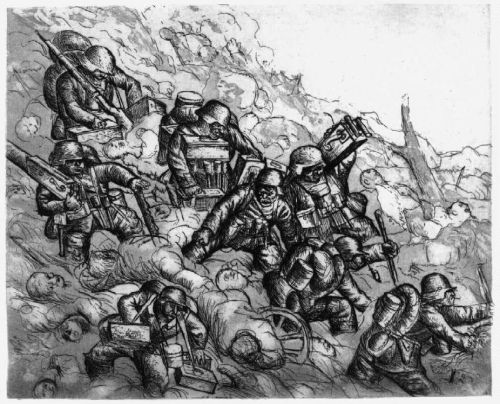

The result of these changes has been to make it rare to see extreme or disturbing images of war in news media. Though, as Taylor states, ‘the bodies of allies and enemies are central to warfare’ [Taylor, p.157], they are consistently hidden or obscured. Stylisation of images, for example showing blood instead of actual injuries, and deflecting the attention of images to other subjects such as weapons and technology (what Stahl calls ‘technofetishism’ [Stahl, p.28]) are two ways this is achieved without appearing to scrimp on reporting events.

Ultimately, the machinery of war has become more important than human bodies, the logical result of long standing military rhetoric which connects war to ‘a basically empty, amoral space’ [Taylor, p.158] and which depersonalises soldiers into parts of a mechanism. Thus the tragedy for an audience of witnessing their own troops dying and the ethical problems of seeing enemies killed is lessened.

———-

Short bibliography:

John Taylor, Body horror

Roger Stahl, Millitainment Inc.

Phillip Knightley, The First Casaulty