On Ruin Value

I feel slightly guilty when I post something which is not directly related to photography, but then I have to remind myself that this isn’t actually a photoblog, it’s simply a blog for things that I find interesting. On that note I recently came to this interesting essay on Sebald, recent German history and the architectural concept of ruinenwert, or ruin value via a friend. Ruinenwert is the idea of constructing a building with the intention that it should look aesthetically pleasing as a ruin, as a future fragment of the original building.

Sebald wrote that when we see a huge building ‘we gaze at it in wonder, a kind of wonder which in itself is a form of dawning horror, for somehow we know by instinct that outsize buildings cast the shadow of their own destruction before them, and are designed from the first with an eye to their later existence as ruins.’ Judging by some of the architects I’ve met I’m not sure how many of them possess the modesty to entertain the idea of their creations existing as ruins, however I am aware of two who definitely did.

Model of the ruins of Pompeii

One was Albert Speer (1905-1981) who developed the concept of ruinenwert while designing buildings for the 1936 Berlin Olympics and articulated the idea in the essay Die Ruinenwerttheorie. For Speer the possible appearance of his buildings as ruins was important because he saw them potentially inspiring future Germans in the same way the ruins of ancient Rome were integral to the myth building of Italian fascism. Heretical though it might have been to suggest that the Nazi era mightcome to an end, it was also a tacit recognition of the power of the mighty remains of one civilisation to inspire the asthetics and ideology of another. It’s an obvious irony that despite the massive destruction soon wrought on Germany, many of these buildings did indeed survive, the Detlev-Rohwedder-Haus, which now houses the German finance ministry, is one notable example.

Earlier though was Sir John Soane (1753–1837), who frequently commissioned paintings of his buildings as ruins. For Soane, who like Speer drew inspiration from antiquity, this practice placed his buildings in the same lineage as those he admired. For example in this drawing of the Bank of England, which turned out to be strangely pre-emptive, as at the start of the twentieth century Soane’s beautiful interiors were ripped out and replaced leaving only the exterior walls of the bank remaining. He also discussed constructing his own home with a thought to its latter ruination, in the essay Crude Hints, he wrote ‘O man, man, how short is thy foresight. in less than half a century – in a few years – before the founder was scarcely mouldering in the dust, no trace to be seen of the artist within its walls, the edifice presenting only a miserable picture of frightful dilapidation’. Perhaps these words lingered on his mind, as Soane later secured an act of parliament before his death to preserve his home as a museum.

Ruins of Coventry Cathedral

Recently I read that the now shelved plans for a vast nuclear waste dump under Yucca Mountain, Nevada had included a call for designs for warning signs that would last 10,000 years. Intriguingly this is a fraction of the time that they would really be required to survive if they were to warn of the buried waste until after it had ceased to be dangerous, not to mention that like early archaeologists encountering an Egyptian ruin, those signs might well be the remnants of a forgotten, inexplicable civilisation, the messages on the signs might have become meaningless and untranslatable within that time. By contrast at the Onkalo nuclear waste site in Finland, designers have tried to find a balance between making the site impossible to find and access, and leaving enough visual clues for anyone who might find it about the nature of what it contains. One proposal for how to do this suggested carving a copy of Munch’s The Scream into the entrance.

I think I find the idea of ruinenwert fascinating partly because it sheds light all creative practice, not just architecture. All things have a lifespan and are subject to disintegration and decay, even in an age where digitisation appears to offer the equivalent of immortality for media like photographs and text. Digital technology is of course far more sensitive and susceptible to the ravages of time than say a stone hieroglyphic. Similarly all created things are liable to be seen and understood in drastically different contexts to the ones in which they were originally located. One wonders what might remain in a thousand years of today’s culture, let alone in ten thousand years. What strange perspective on our culture might future archaeologists have from our surviving ruins, particularly if all that remains are underground caverns housing thousands of tens of tons of deadly waste, will these be our pyramids?

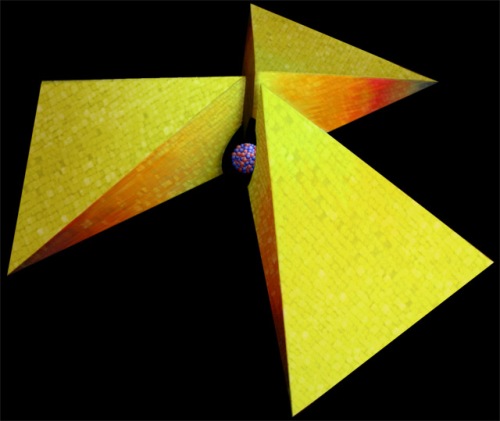

Concept for Yucca Mountain warning sign by Yulia Hanansen

Ruinenwert seems to be both so profoundly egotistical and yet still requires the recognition that even the most sturdy, long standing building is just a flicker that by comparison to the landscape in which it is constructed lasts only for a moment. Shelly noted the transience of passing empires in the poem Ozymandias, describing the statue of a king lying shattered in a desert wasteland. Less well know is Smith’s poem of the same name, written at the same time, and dwelling on similar themes but relating them more directly to the present, as British interests overseas were expanding into what would become an empire occupying almost a quarter of the world. He suggested that perhaps one day:

‘Where London stood, holding the Wolf in chace

He meets some fragment huge, and stops to guess

What powerful but unrecorded race

Once dwelt in that annihilated place’.